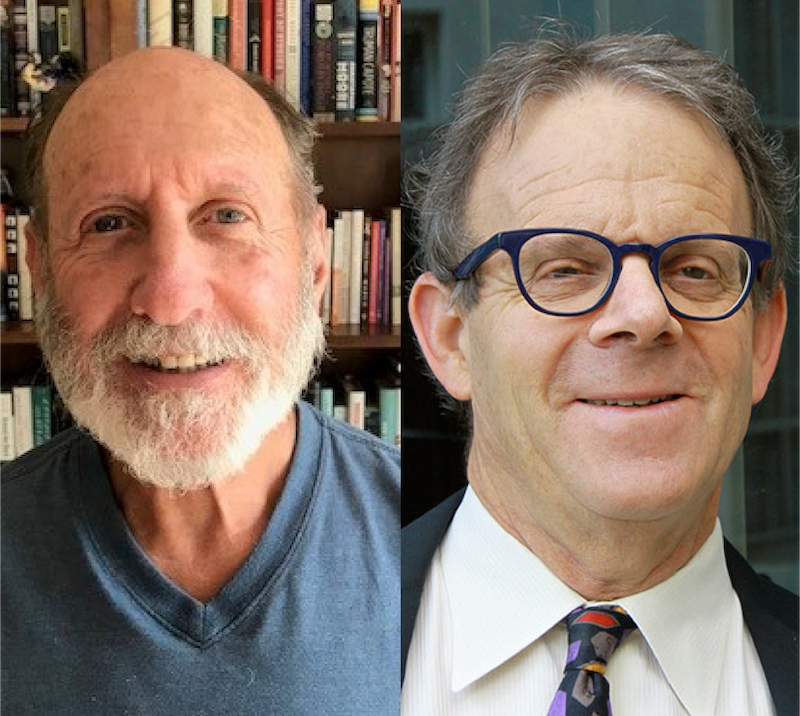

Bob Solomon taught at Yale Law School for decades before moving to UC Irvine as a Clinical Professor of Law. Henry Weinstein is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Lawyering Skills at UC Irvine. They are teaching “Law & Popular Culture: How Films, Television, and Podcasts Shape Our Image of the Law” in Lafayette with us this fall.

You taught this course at UC Irvine Law for years. What was the inspiration?

Henry: Back in 2015, Bob and I had offices across the hall in the law school. One day he came in and asked if I’d like to teach a class with him. He laid out the idea, and I said, “That sounds great.” We started plotting it out from there.

Bob: For years, students talked about wanting a film festival. We’d help them with ideas, but exams got in the way and it never happened. So Henry and I began making our own film lists. He pushed me toward documentaries like The Central Park Five, while I leaned on classics like Anatomy of a Murder and To Kill a Mockingbird.

Henry: We developed weekly themes over time. One week might be on ethics — or the lack thereof. Another compares documentary and docudrama versions of the same case, like The Central Park Five and Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us. We also cover lawyers and journalists confronting power, and end with the Holocaust and Holocaust denial. The themes help anchor a rich discussion.

Bob: Each year after we taught it, we’d ask students what worked and what didn’t. For example, our friend Erwin Chemerinsky thought they’d love Jagged Edge and hate Adam’s Rib. He was completely wrong — they disliked Jagged Edge but enjoyed Adam’s Rib.

We also learned that while lots of people of our generation saw Atticus Finch from To Kill a Mockingbird as the model lawyer, students today don’t. Many women students say Elle Woods is their inspiration.

Elle Woods from Legally Blonde?

It surprised me, too, but her character clearly resonates with them.

Was Atticus Finch an inspiration for either of you personally?

Bob: I respected Atticus, but the reason I went to law school was the Vietnam War and my involvement in civil rights from a young age. Still, I thought Atticus was remarkable. But when I joined a New Haven reading group mostly made up of young Black professionals, they saw him as a “white savior.” That changed how I viewed the film. One of the readings Henry and I assign is Roxane Gay’s piece: “Atticus Finch is Everyone’s Hero. Not Mine.”

Henry: I’m a few years older than Bob, and I’d say the civil rights movement was the primary reason I went to law school, too. We often paired Just Mercy with To Kill a Mockingbird in our course — both set in Alabama, even the same town. The irony was overwhelming. I’m not down on Mockingbird, but I do think it's rarely looked at critically. Some argue Atticus was a failed savior, and in a way, I agree — he tried heroically, but the system was too deeply racist.

What films or stories come closest to portraying the real legal system?

Henry: That’s tough. One that always stands out is the podcast In the Dark, about a Black man in Mississippi tried six times for the same crime. Even Brett Kavanaugh wrote the SCOTUS opinion overturning the conviction. The DA was re-elected afterward. That story feels unbelievably real.

In When They See Us, some scenes are fictionalized — especially Corey Wise’s storyline and a dialogue with prosecutor Linda Fairstein, which resulted in a defamation lawsuit — but they have a painful ring of truth based on my experience as a journalist and law professor.

Bob: Spotlight also hits hard — especially those wrenching interviews with survivors. It’s one of the best films about journalism ever made. And it doesn’t ring false. We also discuss Presumed Innocent and Philadelphia — both films that are raw and emotionally powerful, even if highly stylized.

Do you explore what’s legally accurate in the films you show?

Bob: Constantly. In Anatomy of a Murder, there’s a scene where a witness is cross-examined about his criminal past. Some questions you can legally ask, but some you can’t — like about juvenile records. I used to teach Evidence, and I’d show that scene and have students break down what’s admissible. The same with Philadelphia — you can't ask someone about going to a porn theater to imply they “deserved” AIDS. But Hollywood often does this.

Henry: You see both great and terrible lawyering. It becomes a lesson in itself.

Bob: I tell students if you’re not googling the judge or your opponent, you’re committing malpractice in the modern world. You’ve got to know who you’re dealing with. I knew a lawyer in Connecticut who wore expensive suits every day, but when he had a jury trial, he’d show up in chinos and a tweed jacket. He knew how to read a room.

If you could put one fictional lawyer on your legal team, who would it be?

Henry: Raul Julia’s character in Presumed Innocent. Smart, cagey, he never breaks the rules — but he walks right up to the line. Jimmy Stewart’s character in Anatomy of a Murder is more clever than he seems. There's a great moment where he schmoozes the judge by talking about fly fishing — that’s lawyering, too.

Bob: That’s true. Practicing law isn’t just about legal arguments — it’s relationships. Knowing your judge, your opponent, even your probation officer. I once asked a probation officer about her daughter before a hearing. A young lawyer I was with looked confused. I said, “I’m practicing law.”